We no longer present Paul van Nevel, to whom we owe a unique work on the choral repertoire and so many unexpected discoveries. At the helm of his Huelgas Ensemble, van Nevel recorded Simone de Bonefont’s Messa pro Mortuis. This album Cyprès won in ICMA’s Early Music category. ICMA jury member Pierre-Jean Tribot (Crescendo) made the following interview with the conductor.

We know very little about Simone de Bonefont, except that he was a canon and singer at the Cathedral of Clermont-Ferrand. How did you discover this composer?

We know very little about Simone de Bonefont, except that he was a canon and singer at the Cathedral of Clermont-Ferrand. How did you discover this composer?

I was researching choral books at the Austrian National Library in Vienna. I came across a book by the publisher Nicolas du Chemin, published in Paris, which presented this work by Simone de Bonefont. I immediately made some transcriptions of parts of the Mass and was seduced by this music, especially by its polyphonic richness. I then waited for the right moment to program and record it!

In the booklet of the album, you explain that this work is « an important link in the tradition of the liturgy for the dead, from Ockeghem to Palestrina ». Can you explain us this point of view?

We know of other Masses for the dead from this period, from the one composed by Johannes Ockeghem to the one written by Palestrina at the end of the Renaissance. We must also consider the works of Jean Richafort with his Requiem for six voices in memory of Josquin Des Prés and the Requiem for four voices by Pierre de Manchicourt. But in the end, there are not so many Masses of the Dead. Thus, neither Josquin Des Prés nor Antoine Brumel composed any. In this context, the work of Simone de Bonefont stands out for its originality. Certainly, she uses the plainchant, but she confines it to the first voice, which is unique and gives an unexpected effect.

You have highlighted Simone de Bonefont with four other composers: Arnold von Bruck, Jacobus de Kerle, Orlandus Lassus, Nicolas Gombert. How did you select these program complements?

I looked for what could be put in parallel with this Requiem, which proves to be very meditative and profound, with a very pure aesthetic that makes one think of the plainchant through its melodic evolution. I started with the idea of putting forward another text that speaks of the relationship between death and hope for the future after death: eternal light. I turned to the very beautiful text ‘Media vita in morte sumus’. It is a text which, by its depth and its meditative aspect, can take place next to Bonefont’s Requiem. It happens to have inspired several composers and I have chosen four of them. The first composition is a work by Arnold von Bruck from Bruges, the text is a translation from Latin to German by Luther’s hand. The three other works, by Jacobus de Kerle, Orlandus Lassus and Nicolas Gombert, are masterpieces of the Franco-Flemish repertoire.

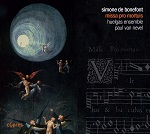

The illustration of this album proposes a detail of a painting by Jérôme Bosch: Ascent of the Blessed towards the Empyrean (detail of Visions of the Beyond). In what way does Bosch’s universe extend the musical program?

Jérôme Bosch is a rather profane painter. However, the detail of the painting highlighted on the cover has a great evocative force. It is about the dead contemplating eternal light, and the latter is here radiant and dazzling!

You are always most active in exploring the repertories. What are your next recording projects?

There are many! Next fall, Sony will release a box set of three discs recorded live in concert during the first edition of our Talant Festival near Dijon in Burgundy. All of our seven concerts have been recorded, and a selection will be the basis of this box set. We will also release an album entirely devoted to anonymous English works from the 13th and 14th centuries. The public will be able to discover that these English compositions from the Middle Ages have nothing to do with the style of works composed on the continent. Finally, we are working on a recording of Pierre de Manchicourt’s Motets for six voices.