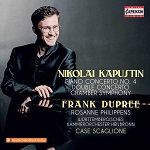

German pianist and conductor Frank Dupree has won the ICMA (International Classical Music Awards) prize in the Assorted Programs category with a CD of concertos and a Chamber Symphony by Nikolai Kapustin. Remy Franck talked with the musician.

Kapustin’s music combines jazz and classical music. The interpreter has to be able to reproduce this mélange. Is that actually difficult?

I grew up as a classical pianist and enjoyed a really classical piano education. Through my drum teacher, whom I had since I was a little boy, I got to know jazz and also African and Latin American music. As a teenager, I combined both and played a lot of jazz in addition to classical music, including Gershwin and Kapustin. For me, Kapustin is the composer who lies exactly in between. Of course, everything is written out in his music. But only if you know the basic elements of jazz, free playing, improvisation, then you can play his music as he intended. The content is jazz, even if the form is classical. Kapustin is a perfect fusion of classical music and jazz.

Now improvisation, which used to be commonplace in classical music, has somewhat gone out of fashion.

Yes, and that is truly a pity. Of course, it’s great if you can play everything according to notes, but I also find it nice to play a piece spontaneously on the piano, without notes and without practicing for hours beforehand. I often do that for myself, to get into the groove or in between, to clear my head again. And I sometimes arrange the encore after a piano concert as a free improvisation. For example, I take some material from the Schumann concerto and improvise freely on it. And I notice that the audience reacts very strongly to this, because we all like this spontaneity. And I can say: I’ve never played it like that before and I’ll never play it like that again, that was a snapshot. That’s something precious in a concert. Kapustin actually does the opposite in this sense, because he ‘composes’ improvisation, and in fact he does it par excellence. I really don’t know any composer, apart from perhaps Beethoven, who could put improvisation down on paper so well.

Yes, and that is truly a pity. Of course, it’s great if you can play everything according to notes, but I also find it nice to play a piece spontaneously on the piano, without notes and without practicing for hours beforehand. I often do that for myself, to get into the groove or in between, to clear my head again. And I sometimes arrange the encore after a piano concert as a free improvisation. For example, I take some material from the Schumann concerto and improvise freely on it. And I notice that the audience reacts very strongly to this, because we all like this spontaneity. And I can say: I’ve never played it like that before and I’ll never play it like that again, that was a snapshot. That’s something precious in a concert. Kapustin actually does the opposite in this sense, because he ‘composes’ improvisation, and in fact he does it par excellence. I really don’t know any composer, apart from perhaps Beethoven, who could put improvisation down on paper so well.

Will we hear more Kapustin from you?

In addition to the CD with concertos, we have now also released our Blueprint CD with piano solo pieces by Kapustin. On this CD we have supplemented the original piano part with an instrumentation of double bass and drums, in order to bring Kapustin even closer to jazz, where I think he really belongs. His music offers many creative possibilities. I played these piano works solo at the Lucerne Festival 2021. By the way, it was the first time Kapustin was performed at the Lucerne Festival. Between his jazz preludes, I kept improvising and thus transitioned from one piece to the next. I did a similar thing with the Variations. Kapustin wrote these Variations on the original melody that Igor Stravinsky used at the beginning of his ballet music Le Sacre du Printemps. As an intro to Kapustin’s Variations, I then played jazz improvisations on Stravinsky themes from the Sacre myself, off the top of my head and very spontaneously. My goal was that at some point the audience could no longer tell exactly where the improvisation ended and where the composition began.

But you are also a conductor?

Yes. I also conduct the Chamber Symphony on the first Kapustin CD, of which there was no complete recording until now. When I conduct, of course, the score is there. But even then I never try to always make the same movements, in order to tease out spontaneity in the orchestra that way as well.

In 2012, you were awarded First prize at the International Hans von Bülow Competition for a Beethoven interpretation as pianist and conductor. I keep noticing that this dual function sometimes works well, but perhaps even more often it doesn’t. Where are the limits, what is allowed, what is not allowed?

For me, this dual function is possible above all with classical works and modern compositions. Shostakovich’s Piano Concertos No. 1 and 2 work well. Whether I would conduct a Kapustin piano concerto from the piano, we will see. I would rather not do a Brahms concerto in that dual capacity. There is already so much symphony in it, and on the other hand, the piano part alone is also very large. You actually have almost two orchestras. One of them is the piano.

And what’s the point of conducting a suitable piece from the piano?

I do it because I really love it! I had the honor of studying conducting with Peter Eötvös. It was he who suggested this double role to me. Working with the orchestra is very important to me. It is very exciting to see how everything develops from the first rehearsal to the concert. In the first rehearsal, I am 80 percent conductor, because then it’s mainly about the orchestra work. The nice thing is that when I’m conducting from the piano, I can transfer my interpretation as a soloist directly to the orchestra. In concert, the ratio is reversed. Then I am 80 percent the soloist, but I always remain deeply involved in the orchestra with my eyes, ears and body. And I am in constant contact with the musicians. That is a wonderful enrichment for both sides. It’s like chamber music on a large scale.

But chamber music is something you like to do. Your latest CD with violist Timothy Ridout was also nominated at the ICMA.

Again, that’s a whole different area. And in the case of the CD with Timothy Ridout, there is also the song. I make a distinction in my piano playing between playing chamber music and song accompaniment. In song, or as here in duo with the viola playing the vocal part, I have to prepare a bed of sound. With chamber music, I’m thinking of Prokofiev, for example, you can already reach into the keys differently. For me, it’s really a matter of separating the individual genres, solo, chamber music, song accompaniment or concertos with orchestra, from each other in terms of sound just as much as the different epochs. Beethoven is not Ravel, and even Schumann in the Piano Concerto is different from the Schumann in the Dichterliebe.

Nevertheless, won’t there perhaps be a focus at some point in your career? More conducting, more chamber music? After all, there are pianists who suddenly only conduct.

At the moment I enjoy the variety. I enjoy it when I play a concert with a trumpet player, the next day a Beethoven piano concerto, and then I can conduct again. If I had only piano recitals for a month, I would miss the orchestra. And vice versa. I’m very drawn to the piano, but so are chamber music and concertos with orchestra. I would be happy if I could continue this mix. Classical music alone is already very diverse, and then jazz is added to that for me, with again very many styles.

But that’s where you differ from many others. Many soloists often only offer a limited repertoire for a season via their agencies, and then they play just one or two piano concertos all over the world. Why do they do it this way? Is the constant change of styles and genres dangerous?

I can understand specializing. It may make sense to focus on one theme, because often a theme in itself offers a great variety. When I look at Beethoven, I see all the music and possibilities there are that you first have to understand. And of course I can know more about a precise piece by Beethoven if I know all his pieces.

For me, the constant change between styles and genres has always been part of being a musician. As a child, I jumped from drumset to piano: one moment I was playing rock’n’roll, the next moment Bach. Today, too, my main concern is to show connections, to build bridges between genres and to create new perspectives, to look at music from a new angle.

What does the ICMA award mean to you?

For me personally, this award is a very great joy and honor. Recording the great music of Nikolai Kapustin has long been an affair of the heart for me. I would like to say a big thank you to the Capriccio label, the Württemberg Chamber Orchestra, conductor Case Scaglione and my partners Rosanne Philippens and Obi Jenne, without whose special qualities the realization of our Kapustin CD would not have been possible. A great wish is to bring Kapustin’s works to the stage and to share this unique, hardly heard repertoire with many listeners and that we really rock the concert halls!