The repertoire for the viola is limited. But it is growing – also thanks to Sào Soulez Larivière. The viola virtuoso, born in 1998, loves to arrange works for his instrument and experiment with the contemporary. His musical brilliance and versatility have already earned him several awards. This year he is the recipient of the ICMA Young Artist Award. In February, he took time for an interview with ICMA jury member Frauke Adrians (Das Orchester) in his current hometown of Berlin.

Dear Sào Soulez Larivière – you here in Berlin? I thought you would have been in Kronberg long ago.

At the moment I am in both places! Last year I completed my bachelor’s degree in Berlin at the HfM Hanns Eisler with Tabea Zimmermann, and now I’m sort of commuting between Berlin and Kronberg Academy, where I’m currently doing my master’s degree. There, too, I continue my lessons with Tabea Zimmermann.

Is she your role model – perhaps even in the sense that you would like to teach like her one day?

Oh yes! It is a very great privilege to study with Tabea Zimmermann. I am always fascinated and thrilled by how true she remains to the music and how well she is able to convey this to her students.

From my side, I have already been able to help some students in class and have noticed how much you learn about each other – and even about yourself! I am very grateful for that and want to continue.

You’re in your mid-twenties, but your viola is even younger than you are: you play on an instrument made by Frédéric Chaudière in 2013. Is such a ‘fresh’ viola the right one for you and for the repertoire, which is usually already a good hundred years old, that you primarily play?

Most definitely. My viola is just right for me: in terms of size, but also in terms of sound. We sought each other out and found each other, so to speak! A musician realizes very soon whether he has the right instrument; after all, he spends his entire life with it. I wouldn’t say that an older instrument is necessarily better than a modern one, they just have different qualities. In the end, it really depends on what unique sounds the player is looking for.

« Too fresh » is certainly not what my viola is about! The exciting thing is that we are building something new together.

How did you come to play the viola in the first place?

Actually, I started playing the violin when I was little. Like my older sister, who is a violinist, I studied violin intensively with Natasha Boyarsky at the Yehudi Menuhin School in England, but later tried out the viola in chamber ensembles and the orchestra along the way. And that’s when I fell in love. That was the instrument for me! The timbre, the range of the viola: all that was much closer to my heart than with the violin. Of course, this change of instrument also brings trouble, you have to get along with a new clef, for example, but then you learn that. I especially liked the feeling of being in the middle within a string ensemble. As a violist, you use your ears more than your voice, so to speak!

But as a soloist on the viola, you don’t have nearly as much repertoire at your disposal as a violin soloist…

Of course, but that is not necessarily a disadvantage – rather the opposite! As a violist, you are constantly challenged to explore the possibilities of your instrument and to open up new repertoire. We borrow a lot from the violin, the cello, even the clarinet. I really enjoy arranging for the viola and trying contemporary things, and when I program concerts, I enjoy the feeling of pushing the boundaries of the repertoire. The idea that we today’s musicians are true pioneers, helping to shape what is playable for future generations of musicians, I think is fantastic.

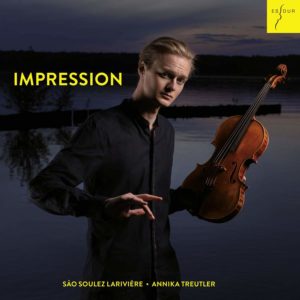

You make chamber music – also together with your sister Cosima – you have recorded a Tchaikovsky and Dvorak CD with the Frielinghaus Ensemble, but you have received excellent reviews especially for your debut album with works by Hindemith, Debussy and Rebecca Clarke, among others, which you recorded with pianist Annika Treutler. Is there a focus in your work on fin de siècle music?

You make chamber music – also together with your sister Cosima – you have recorded a Tchaikovsky and Dvorak CD with the Frielinghaus Ensemble, but you have received excellent reviews especially for your debut album with works by Hindemith, Debussy and Rebecca Clarke, among others, which you recorded with pianist Annika Treutler. Is there a focus in your work on fin de siècle music?

Yes, I find that music incredibly appealing. There was certainly a lot of amazing viola music written during that period. It was an aha moment when I discovered that Hindemith’s Sonata Opus 11 No. 4 and Clarke’s Sonata for Viola and Piano were both written in 1919. There is a hint of late Impressionism – it is not by chance that our CD is called ‘Impression’. This music could probably only have been written in this way during this period. That’s what makes it so moving and gives it its modernity to this day.

However, I wouldn’t say that my focus is on a particular era. I am constantly on the lookout for new and exciting repertoire to include in my program.

Now CDs are actually a medium of yesterday. Is it still worthwhile for you and the musicians and music consumers of your generation to bother with these old-fashioned discs, when you can stream almost anything today?

It’s true, a CD certainly doesn’t mean the same thing today as it used to. However, most musicians still try to record CDs. I think the concept of a CD nowadays is more about being able to collect your artistic imagination and ideas and show everyone how far you’ve come on your personal journey.

True, nowadays everyone streams, or almost everyone does, especially the young people are very familiar with platforms like Apple Music or Idagio. But the medium doesn’t change the fact that classical music has little audience among the younger generation. Teenagers and young adults are still not exactly open to classical music, they come to concert halls far too rarely. Something has to change there!

What? And how can you achieve that?

We have to make people understand what’s so special about our live concerts. That it is an experience of extreme concentration and intimacy, where you are completely immersed in listening. There’s something spiritual about that! In my experience, the social media mean that everyone is constantly present virtually, but that concentrated listening and real communication hardly ever take place. I have often thought: Maybe we musicians should go out with our instruments much more often, go to the people, and give them free tickets for our concerts. If we can get just one extra person to come to the concert, we’ve already won something! In general, we should think outside the box a lot more. Here in Berlin, for example, I love playing music in cafés – just for fun. Chamber music doesn’t necessarily have to take place in a real concert hall!

Do you think that might be a general approach to attracting new audiences: out of the concert halls, into life?

In a way, yes. I find the touring business as it is today far too hectic: usually we only have one day at a concert venue, we arrive, do the dress rehearsal, give the concert, and we’re gone again. Musicians should be able to spend more time in one place, and have more opportunity to give outreach concerts to connect with the local community. How else are we going to generate new interest in ourselves and our music?

For almost three years, most musicians were unable to perform in concert halls or anywhere else: The Corona pandemic crippled concert life. How did you get through this time?

Personally, it was a very important time for me. For one thing, I found a more intense, deeper way of practicing. On the other hand, the compulsory Corona break was also a blessing for me mentally. Suddenly I had time to take a deep breath – and to think intensively and self-critically about why I make music and whether I have really found what I want to do in life.

For myself, I can say that I’m more sure of myself now than before: yes, I’m on the right path, yes, I want to make music. I’ve found a better balance between work and enjoying life, and I know that I’m focusing on the right thing. But I also know that other musicians have had a very different experience: many – including some of my acquaintances – decided to give up music as a career during the Corona period, not so much for financial reasons, but because they realized that music could no longer be the center of their lives. Either way, this phase forced a kind of reality check. It was invaluable for me.

You were born in Paris, your mother tongue is Dutch, you feel at home in France and the UK. How come you now live and work in Germany?

It just happened that way! I was looking for the right viola teacher for a while. In the end, I decided on Tabea Zimmermann and Berlin. Fittingly, my sister also lives in Germany, in Hanover. The musician’s life can be quite hard, so it’s an advantage to have relatives and friends nearby so you can support each other. But it’s also a pleasure to work in Germany. You find incredible support and initiatives for classical music and for culture. Whereas a few years ago practically no one at the Menuhin School said that they would like to go to Germany to study, now more and more are coming here from there. There are good reasons for this!

You are widely touring as a soloist; as recently as February 18, you gave a concert at Hamburg’s Laeiszhalle, playing works by Britten and Shostakovich, among others. Is the soloist career right for you? Have you tried an orchestral position as well?

I don’t want to put myself in any particular category. For me, the wonder, the magic of being a musician is to go out into the world and share the beauty of music. In that sense, wherever my viola takes me, I will be happy to be by its side.